5 Orchestration

The targets package runs the correct targets in the correct order (orchestration) and creates new targets dynamically at runtime (branching). This chapter describes the underlying package structure and mental model that gives targets its flexibility and parallel efficiency.

To orchestrate targets, we iterate on the following loop while there is still at least one target in the queue.

- If the target at the head of the queue is not ready to build (rank > 0) sleep for a short time.

- If the target at the head of the queue is ready to build (rank = 0) do the following:

- Dequeue the target.

- Run the target’s

prepare()method. - Run the target’s

run()method. - Run the target’s

conclude()method to updates the whole scheduler. - Unload transient targets from memory.

The usual behavior of prepare(), run(), and conclude() is as follows.

| Method | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

prepare() |

Announce the target to the console, load dependencies into memory, and register the target as running. |

run() |

Run the R command and create an object to contain the results. |

conclude() |

Store the value and update the scheduler, create new buds and branches as needed, and register the target as built. |

The specific behavior of prepare(), run(), and conclude() depends on the sub-class of the target. For example, run() does nontrivial work in builders (stems and branches) but does nothing in all other classes. The conclude() method is where stems and patterns update the scheduler and spawn new buds and branches dynamically. Two of the most important responsibilities of conclude() are

- Decrement the ranks of downstream targets in the priority queue.

- Insert new targets dynamically.

For patterns, conclude() is called twice: once to spawn branches, and then again when all the branches are done.

5.1 Decrement the ranks of downstream targets in the priority queue.

The conclude() method decrements ranks in the priority queue to signal that downstream neighbors are one step closer to being ready to build. Most targets decrement all their downstream neighbors, but a pattern only decrement the neighbors that branch over it. This behavior for patterns is key because it allows future patterns to quickly define new branches before the current ones even start running, which contributes to parallel efficiency.

5.2 Insert new targets dynamically.

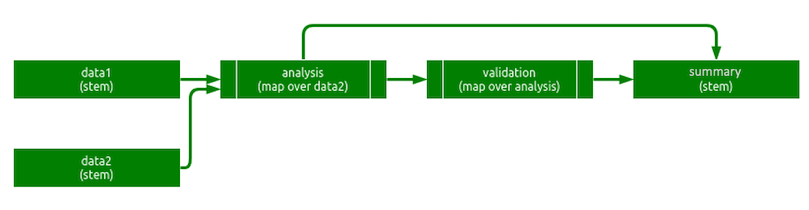

targets creates new targets dynamically when stems and patterns conclude. To illustrate, let us use the following example pipeline.

# _targets.R

library(targets)

source("functions.R") # Defines all the functions below prefixed with "user_".

list(

tar_target(data1, user_data1()),

tar_target(data2, list(user_data2_slice1(), user_data2_slice2())),

tar_target(analysis, user_analyze(data1, data2), pattern = map(data2)),

tar_target(validation, user_validate(analysis), pattern = map(analysis)),

tar_target(summary, user_summarize(validation)) # Does not map over validation.

)In prose:

- The

dataanddata2targets are starting datasets. - The

analysistarget maps over the rows ofdata2and performs a statistical analysis on each row. All analyses use the entirety ofdata1. - The

validationtarget maps over the analyses to check each one for correctness. - The

summarytarget aggregates and summarizes all the analyses and validations together.

Graphical representation:

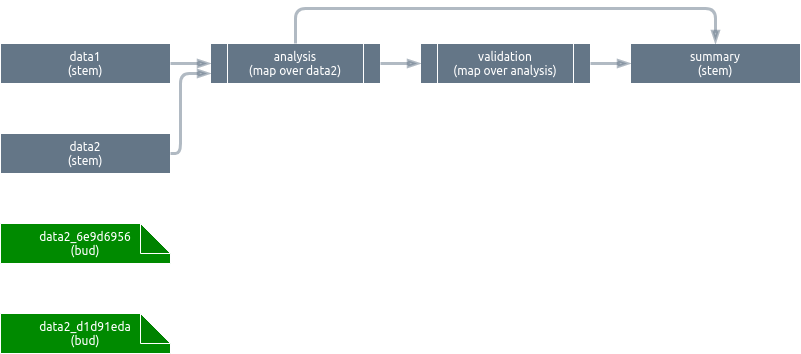

5.2.1 Insert buds

Upon conclusion, data2 creates buds to help its downstream neighbor analysis map over it later on. data1 creates no buds because no pattern branches over it.

To insert the buds, we:

- Create a new junction with the names of the buds to create.

- Create new bud objects, each containing a slice of

data2’s return value. - Insert the buds into the pipeline object.

We do not need to update the scheduler because the parent stem of the buds already completed. In other words, buds are born built. They exist as separate data objects in memory, but they have no dedicated storage.

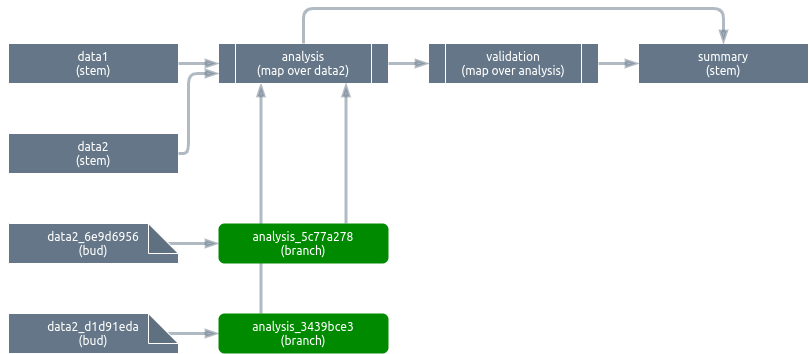

5.2.2 Insert branches

With the buds in place, the analysis pattern can now create branches that depend on each of the respective buds of data2. After they run, the branches exist as separate data objects in memory and storage. The full aggregated analysis pattern is not needed, so it is never created.

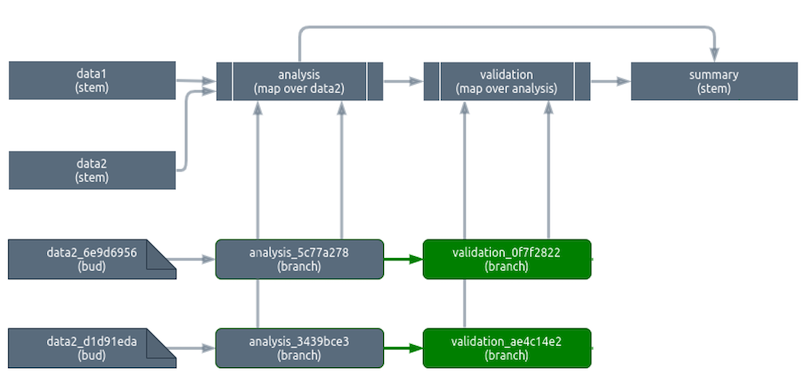

As soon as these first branches are created, we can create the branches for validation. It does not matter if analysis_5c77a278 and analysis_3439bce3 are both still queued. In addition, as soon as analysis_5c77a278 is built, validation_0f7f2822 can start building regardless of whether analysis_3439bce3 is complete. This is a major source of parallel efficiency.

Notice that we never draw edges from the validation_* branches to summary. This is because summary does not map over validation, so it automatically takes in all of validation as an entire aggregated pattern. In the prepare() method of summary, validation is constructed from its individual branches kept in memory while it is needed. Unlike the validation_* branches, the aggregated validation pattern does not persist in storage.

The fine details of the branching algorithm are as follows.

- First we create a junction to describe the branches we will create based on the user-supplied

patternargument totar_target(). - Create and insert those new branches into the pipeline.

- Draw graph edges to connect the branches to their individual upstream dependencies (buds or branches).

- Insert graph edges from the new branches to their parent pattern. Some targets may use the entire pattern in aggregate instead of iterating over individual branches, and this step makes sure all the branches are available for aggregation before a downstream target needs to use the aggregate.

- Push the branches onto the priority queue. The rank for each branch is the number of upstream dependencies that still need to be checked or built. 1. Increment the priority queue ranks of all downstream non-branching targets by the number of new branches just created minus 1. This ensures all the branches complete before any target calls upon the entire aggregate of the pattern.

- Register the branches as queued in the scheduler.

- Push the pattern itself back onto the queue, where the priority queue rank now equals the number of branches minus a constant between 0 and 1. (The subtracted constant just ensures the pattern gets cleaned up as soon as possible.) This step ensures we revisit the pattern after all the branches are done. At that moment, we decrement the priority queue rank of every downstream target that depends on the entire aggregated pattern (as opposed to just a single branch). This behavior drives implicit aggregation, and it ensures we do not need a special

combine()pattern directive to accompanymap()andcross().